A Reflection on Art and Video Games

With the recent passing of Nintendo’s Satoru Iwata, many mourners found solace contemplating his lifelong philosophy on game making, which is a gleaming allegory of the relationship between art, artists, and art lovers.

Let’s Define Art

One of the most enthralling courses I had to chance to attend in college was an art history series of lectures taught by a painter and a philosopher. The goal of the course was not only to expose us to a variety of art movements, but also to ask ourselves to develop a personal argumentation that can be applied to any medium, and to explain what makes a crafted piece an art chef-d’œuvre.

Despite being such a daunting search, I’m comfortable enough to share my findings. An art masterpiece comes from an authentic spark of the imagination, infused with a creative geist, and is crafted to such a level of perfection that it creates a strong emotional bond between the piece and its audience.

Storytelling is probably the oldest art known to man that hasn’t lost its relevancy over thousands of generations. It shows the importance of connecting with one another on an emotional level.

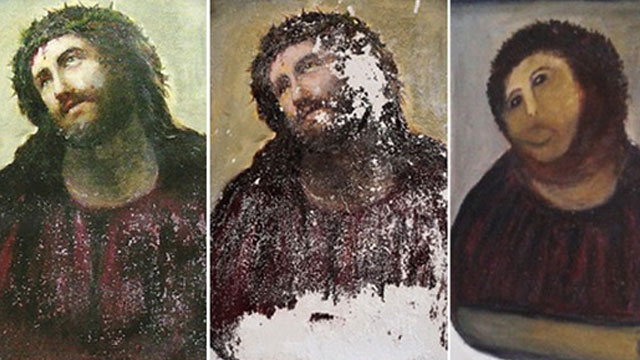

Craftmanship is a pillar of any artistic endeavor. Anyone can pick up a brush and start painting, but without mastering the tools of the trade, creating something meaningful is hard to attain.

Propaganda will only ever be craftmanship, as it’s denuded of an authentic creative geist; it is manufactured to promote a political ideology, which will never result in a genuine emotional bond.

Some will argue that art needs to have a purpose, and carry a message; that it’s the only kind of art worth anything.

I vehemently disagree with this notion.

Let’s point out that this higher-purpose imperative is common across all the authoritarian regimes of the twentieth century where the sole purpose of art, and the only one allowed, is propaganda. The Nazis coined the term ‘Degenerate Art’ to talk about any created artwork that didn’t promote the glory and ideals of the Third Reich.

The problem with a piece manufactured only to convey a single message, is that it is meant to use the same emotional trigger with everyone. What qualifies the strength of an emotional bond is the authenticity and personalization of the bond. When a piece of art is released into the world, it takes on different meanings for different people; this is what makes it resonate with each of us in a different, personally meaningful way. Any artificially manufactured bond is bound to be emotionally weak.

Girolamo Savonarola is responsible for the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497 during which thousands of books and paintings deemed unworthy were destroyed.

The säuberungs were the public book burning rallies orchestrated by the Nazi regime to purge Germany from novels their doctrine labelled as degenerate.

Alex Lifschitz destroying a disc copy of Grand Theft Auto V during his GDC speech entitled “The Treachery of Games” calling Rockstar’s masterpiece “hot garbage.”

This notion of righteous, meaningful art taking a stand against degenerate, unworthy garbage, is very prevalent with the gaming press’ indie darlings which views AAA games as abominable junk. The roots of this philosophy is based on superficial projections embracing normative homogenization, which forces a strong hatred for divergent viewpoints and a lack of understanding when it comes to art’s motive: unconditional and passionate love.

Art Stems from Passion

Art is one of the most amazing parts of culture. At the inception of any artwork comes the desire from a creator to share something in the hopes of connecting with other people. One of the oldest art piece in existence, the Lascaux cave paintings, is a testament to this.

Artists are a craftsmen at heart, who have fallen in love with a craft and indulge in the contemplation of works from other craftsmen to assimilate techniques to perfect their own. Nevertheless, that learning process is only second to the enjoyment provided by gazing at skillfully crafted pieces. That is why many filmmakers are more than simple cinephages, they are true cinephiles.

“On my business card, I am a corporate president. In my mind, I am a game developer. But in my heart, I am a gamer.”

Satoru Iwata

“If you want to be a writer, you must read a lot and write a lot. I don’t read to study the craft; I read because I like to read.”

Stephen King

“You can’t make a movie just because you’re a fan; that’s not enough. You’ve got to ask yourself what’s the story; is it compelling?”

J.J. Abrams

And for the exact same reason, when artists create a masterpiece, it is always, in one way or another, a love letter to their art form. It’s never an ego trip, as the focus of their attention is always the artwork, not their own personal glory or fame. They make sure that the product of their sweat, blood, and tears is spellbinding; that their magnum opus is what they would enjoy as fans, owing to the fact that they embrace their own personal fandom for that particular art form.

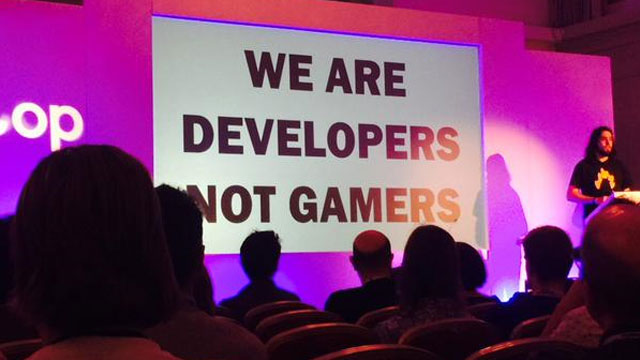

You don’t have to be a gamer to make games, BUT…

Now that we’ve looked at what makes heart so vibrant and meaningful, it’s time to look at the viewpoint of the mainstream indie scene which doesn’t represent the vast majority of indie devs, but is the group with the strongest mediatic clout.

When one starts negating art by separating works into ‘art that matters’ and ‘degenerate art,’ it implies that the craftsman believes in his/her superiority as an artist compared to other craftsmen; that people who do not appreciate what they deem high art are degenerates, too. This is very clear when looking at statements made by some indie devs, who see gamers as inferior human beings and use the term defining game lovers in a pejorative manner.

This has two major consequences: when people who love the craft tend to voice their revulsion to their beloved medium used as propaganda tool, the self-proclaimed cultural elite has to alienate and vilify the unworthy audience. When there is no audience to make the artwork market sustainable, they blame it on the audience lack of cultural intelligence, instead of the lack of appeal of the artwork.

That last consequence is the reason why many of the devs in that mindset are lobbying for their work to be sponsored by government grants. However, they do not understand that government sponsored cultural art projects, like PBS, are mandated to be free from ideological bias.

“These obtuse shitslingers, these wailing hyper-consumers, these childish internet-arguers don’t have to be your audience.”

Leigh Alexander

“You don’t have to ‘be a gamer’ to make games. You just go and make games. You don’t have to pander to your audience.”

Rami Ismail

“Hahaha. We’re so free. Look at us. FUCK GAMES! FUCK GAMERS! FUCK THE GAME INDUSTRY! DIE! DIE! DIE! And rot in hell!”

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn

I once asked a TV news reporter I worked with why she was always frowning in her reports. She told me that she wanted to be taken as a serious reporter, and therefore she couldn’t smile while reporting on serious issues, as if appearances were giving gravitas to her work. The mainstream indie scene has the same superficial outlook on video games: Leigh Alexander infamously said that it is time to have games that are not fun. What she meant, was it is time for video games to tackle serious social subjects and being fun is antagonizing the seriousness of it all. This is equivalent to saying a book about serious matters has to be boring; it demonstrates mistaking tonality for subject as well as misunderstanding artistry and craftsmanship.

A skillful author can turn any boring topic into a fascinating read.

There are so many examples from so many mediums demonstrating that. One of the most heartbreaking movies about the Holocaust is the Italian comedy, La Vita è Bella, directed by the amazing Roberto Benigni, a pantomime genius who made a very tasteful humorous movie about one of the saddest tragedies of mankind. When it comes to gaming, every player who’s ever experienced lag online knows how frustrating it can be. However, in Volition’s Saints Row: The Third, one of the most memorable missions utilizes lag on purpose. In context, this gameplay mechanic is so compelling that an otherwise infuriating phenomenon becomes a ton of fun.

There is no secret. To understand the rules of the craft, you need to love the craft to begin with; do your due diligence to learn by playing video games created by skilled craftsmen and don’t approach their work with a nasty condescending attitude. Just because the tonality of a game is more serious, doesn’t make the gameplay or the game any better or any more compelling. A well executed ludic parody of video games can teach something to anyone interested in making games, but again, it starts by respecting the craft and the ones who admire it.

…Without an Engaged Audience, you are not an Artist

The ideological hug box created by the belittlement of the craft and its audience heightens the sense of entitlement and self-importance of media critics and craftsmen in the clique. It is a warped sense of reality that cannot stand the test of time.

In 1994, the highest rated movie by film critics was Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. It is an absolutely wonderful tour de force; however, art doesn’t belong to apparatchiks, but to the public, and twenty years later, a movie that came out that same year that was ignored by the almighty cultural elite, is now considered as one of the greatest films of all time.

I’m referring to Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption.

What gives the movie penned by Stephen King its pedigree, is the emotional bonds it has created over the years with countless film lovers, not the approval by a small insular community of industry pundits.

The indie diaspora doesn’t grasp that many successful AAA studios have very humble beginnings and attracted the attention of big publishers due to the success of their previous games. They do not have massive budgets because they make junk pandering to gamers; their financial situation is the result of their work resonating with a large audience. To many of these big studios; they cherish that relationship with their audience that they worked so hard to establish.

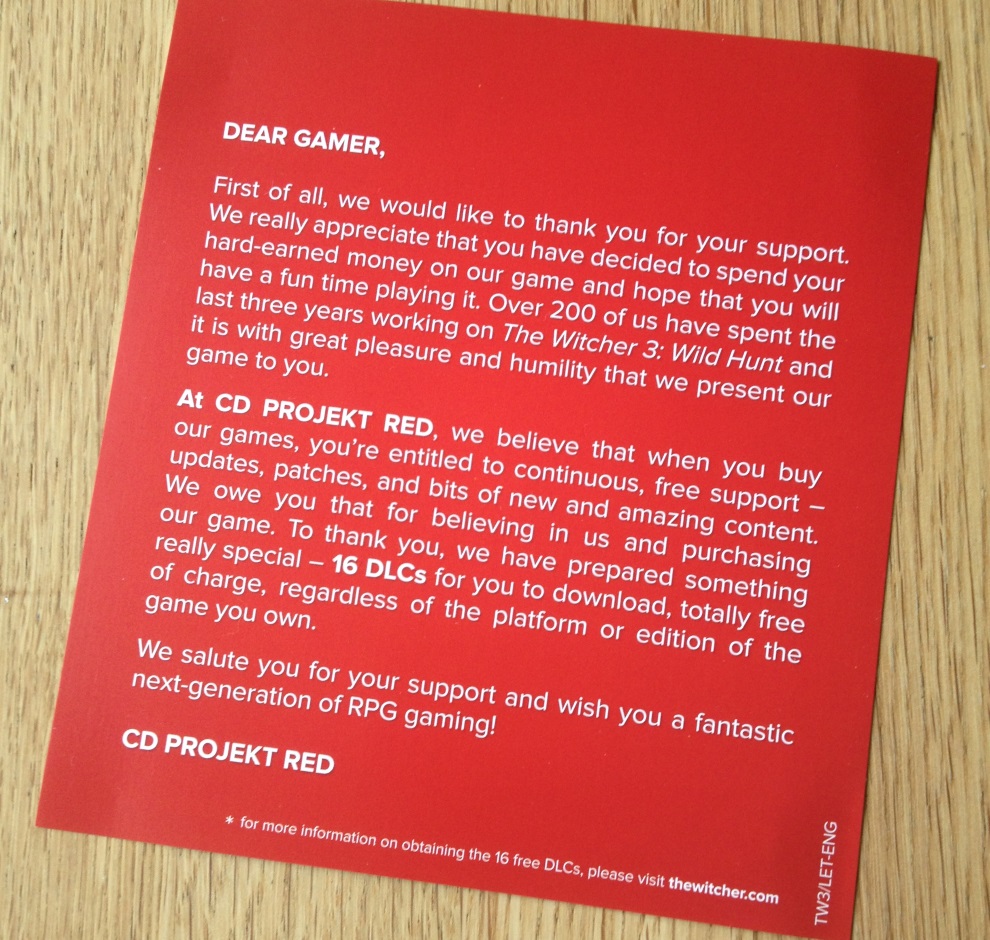

When CD Projekt Red’s game, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, was released, people who purchased the game, including the over a million who preordered it, were gifted with a note expressing the devs’ gratitude.

Where pretentious developers, believing success to be entitled to them, would call it “pandering to the audience,” artists, who’ve had successful careers, understand that anyone fortunate enough to be working in a creative industry owes their livelihood to their audience, and would call CD Projekt Red’s gesture a heartwarming display of mutual respect and humility.

It is not as uncommon as one may think: fans who waited overnight to assist to the StarWars SDDC panel this year were welcomed with hot coffee and donuts brought by the production of the movie. The producers were well aware that even without treats, these fans would go see the movie; that these gesture wouldn’t increase tickets sales; yet they still did it, because they wanted to show their audience that they care and are thankful for their continuous support over the years. This is in no way, shape or form, pandering.

Gaming is an art and is in need of artists. Certain magniloquent and highfalutin indie developers should realize that, even if the customer isn’t always right, having a minimum level of respect for that said customer who cherishes the craft of game making, is a basic requirement for any creative trade.

Being called an artist is a privilege, not an entitlement: it is a title bestowed by an audience, it is not a right the craftsman is due.